Kenya Expands Treatment for People Who Inject Drugs

HIV prevalence rates are elevated among people who inject drugs (PWID) in all parts of the world, and in Kenya the documented prevalence is 18.7%, even higher than regional estimates. Because of the stigma they encounter, this population is also often denied essential health services and support, including antiretroviral therapy (ART).

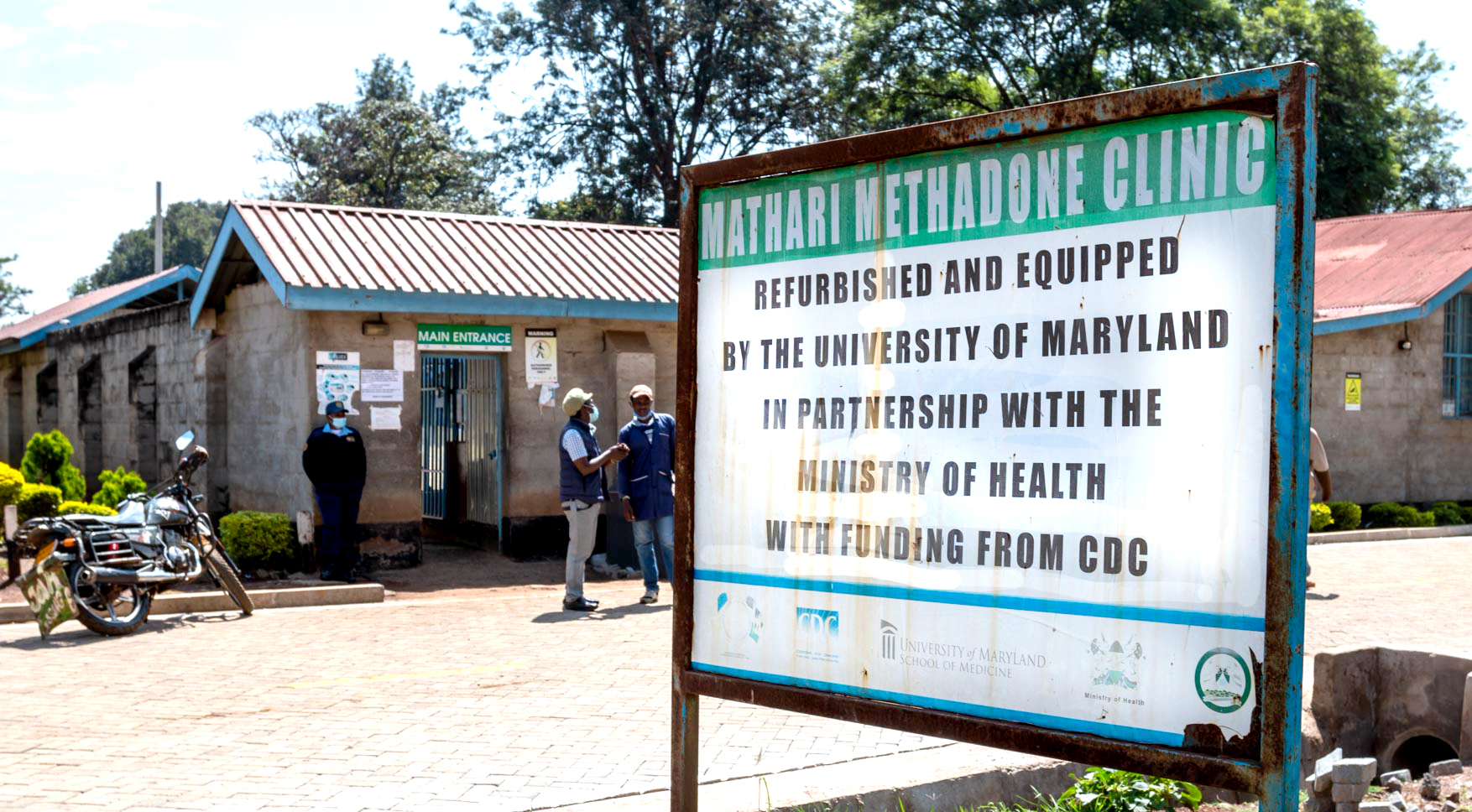

In Nairobi County, Kenya, health authorities have taken action to reduce the spread of HIV among PWID. The first medically assisted therapy (MAT) clinic in the nation to support PWID was established in Nairobi in 2014 with the assistance of the University of Maryland, Baltimore. The clinic was established with funding from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention under PEPFAR as part of Ciheb’s PACT Endeleza Project in Kenya.

The Mathari National Teaching and Referral Hospital in Nairobi was selected by Kenyan health authorities to house this MAT clinic. Mathari is a national teaching and referral hospital that provides psychiatric services and has the resources and expertise in addiction management.

The Mathari MAT clinic offers free integrated services for PWID, including opioid substitution (methadone) therapy; HIV testing services; ART; condom distribution; vaccination, diagnosis and management of viral hepatitis; prevention and treatment of tuberculosis; and overdose prevention and treatment. The therapy centers on harm reduction, which comprises a range of services that mitigate the adverse consequences of drug use and protect public health. Harm reduction acknowledges that people face challenges in freeing themselves from drug use, and that abstinence should not be a precondition for support and treatment.

Cumulative Mathari MAT Uptake 2014-2019

Establishing the Ngara Health Centre Clinic

Establishing the Ngara Health Centre Clinic

The success of Mathari led to the opening of a second clinic in 2017 at the Ngara Health Centre in northern Nairobi, which has a maternity wing. “Ladies coming into the program were expressing a desire to get pregnant,” explained Dr. Tina Masai, clinical psychologist and MAT specialist. “And because they are no longer using heroin, they are more likely to get pregnant.” The Ngara clinic has had 11 successful term deliveries since it opened (Mathari has had 31). Out of the 42, only four neonates had neonatal abstinence syndrome, and this low number can be attributed to the mothers being on methadone treatment at the time of delivery.

Overall, the two clinics have enrolled 2,262 clients. As of January 2021, 1,137 were receiving daily treatment, and 111 have been entirely weaned from treatment. The clinic has achieved viral suppression rates of the clients living with HIV above 95%. “PWIDs really become more stable when they're put on MAT,” said Patrick Eshikumo, Ciheb HIV prevention specialist. “Methadone treatment has produced good treatment outcomes for ART.” Treatment of hepatitis C has been similarly successful, with a 98% cure rate.

Improved psychosocial outcomes are key indicators for assessing the impact of MAT interventions. Of the key psychosocial indicators tracked, MAT has been shown to improve family and community reintegration, stable accommodation, and employment. MAT interventions have also seen a decrease in incidences of violence, as well as crime.

Of note is an increase in unemployment over time for those who have been on treatment for a longer duration. This highlights the need for sustainable livelihoods in order to further enhance client wellbeing.

Role of UMB and Civil Society Organizations

The University of Maryland, Baltimore is known for its technical expertise in supporting PWID and has established MAT clinics in Baltimore. The School of Medicine’s Dr. Christopher Welsh led a team in Nairobi in 2014 to help build capacity and train and mentor staff. This training occurred in Kenya and at the School of Medicine in Baltimore and during visits to established clinics in nearby Tanzania. In addition to helping to start up the clinics, Ciheb continues to support their operation by providing staff resources.

Civil society organizations (CSOs) play a key role in supporting PWID, and in Kenya they were actively engaged prior to the establishment of the Mathari clinic. The groups include the Support for Addictions Prevention and Treatment in Africa, the Nairobi Outreach Services Trust, Médecins du Monde, the Police AIDS Control Unit, and others. The groups worked with county leadership and the National AIDS & STI Control Programme, creating a stakeholder engagement forum that developed national guidelines and standard operating procedures for the clinics. The forums, called MAT linkage forums, remain active and are instrumental in referring clients for treatment at the clinics.

Working with Law Enforcement

"Where the police cooperate with community workers, condom use can increase and violence and HIV infection among sex workers can decrease. Where governments promulgate harm reduction, such as clean needle distribution programmes and safe injection sites, HIV infection rates among people who use drugs can drop significantly.”

Global Commission on HIV and the Law, Risks, Rights & Health, July 2012

Criminalizing drug use increases vulnerability and negatively impacts access to health services among PWID, and it contributes to the spread of HIV, hepatitis C, and tuberculosis. The MAT clinics actively work with law enforcement in Kenya to implement harm reduction and maintain treatment for PWID with positive results, helping to reduce stigma and violence.

Sensitization of police recruits to PWID at the Police Training College in Kiganjo, Kenya.

Sensitization of police recruits to PWID at the Police Training College in Kiganjo, Kenya.

“Police engagement from the onset is a critical and continued element of sensitization,” explained Dr. Masai. “We've been able to have very key police stakeholders who understand MAT, the clinic, and the program comprehensively.” The relationship with law enforcement has grown and expanded awareness and sensitivity. An outcome of this successful engagement facilitated the development of fixed-site dispensing at prisons during the COVID-19 pandemic. These new fixed-site MAT clinics at prisons support not just existing clients but can also enroll new eligible clients at the prison.

Addressing Challenges

One of the challenges faced by the MAT clinics is reaching younger populations. The national Kenyan guidelines exclude people under the age of 18 from methadone treatment eligibility. However, many PWID need treatment when they are younger. “More than 80% of our clients were using heroin before they turned 18,” estimated Dr. Masai. She explained that students at universities are not being reached by the CSOs and are a key population. “Our model requires community referral to the MAT clinic,” explained Dr. Masai. “The model doesn't work for people who don't come from the community and have no desire to engage within the community mechanisms, so it really excludes a large number of people.”

Dr. Masai further explained that another key challenge in sustaining clinic operations is staff resources. This resource gap has largely been filled by UMB. “In the Mathari hospital," said Dr. Masai, "the data office, the lab, HIV testing services, and the entire psychosocial department are manned by UMB-supported staff.”

Eshikumo indicated that another key resource barrier involves the clients themselves. “It's a bit costly for the PWID to come daily. Most of them are coming from far off areas,” he said. Dr. Masai agreed, adding that decentralizing MAT services as a means to reduce client costs is an issue being discussed in Kenya. What is at stake is clients' ability to spend more time developing livelihoods. Dispensing treatment with mobile van units is being considered as an option, which would help reduce the opportunity costs imposed on clients needing treatment. However, the human resources to implement a van unit program are not, as of yet, available.

Notwithstanding these challenges, the MAT clinics in Kenya have played a decisive role in overcoming the barriers that had prevented PWID from receiving treatment. Because of the success and the greater demands that have arisen in the wake of COVID-19, the Mathari hospital was recently designated by the Government of Kenya as a semi-autonomous government agency or parastatal. "Mathari Hospital's designation as a parastatal will pave the way for discussions on inclusion of MAT in the hospital budgeting and forecasting," said Dr. Masai. "This will contribute to its sustainability and build on its achievements."